Country Garden With Sunflowers, 1904 by Gustav Klimt

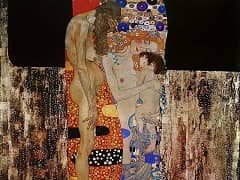

Klimt's art expresses a regressive attitude, a classic middle-class escape mechanism with romantic roots that extends to the television society and cyberworlds of today. The sensitive epicurean Klimt would like to get away: away

from the hectic city of Vienna, away from the crumbling Habsburg monarchy, away from the turmoil of World War I. His art seeks that 'elsewhere,' that utopian place where, as he once wrote, 'fate will let us enjoy pleasure.'

Landscape painting became so important to Klimt from 1898 on (the exhibition covers from 1898 to 1916). He moved toward a vision that was increasingly based on the light, openness, and patterns of nature rather than the formal,

especially linear, complications of narrative and mythology.

In many works throughout this period, the view is of a field or hedge of flowers, or of the leafy and flowered branches of trees pushing out to the edges of the canvas so that little of the sky appears. The point of vision is

intense and uncompromising, forcing the viewer (artist) to hold this incredible abundance in his eye, his brain. In later paintings, from about 1908 on, architecture reenters the scene in views across the lake or in the woods

from Klimt's various vacation studios. It is here that Klimt used opera glasses, telescope, and even telephoto camera lenses.

Gradually, but not always, the multitude of brushstrokes become clustered in shapes with the outlines of flowers, branches, buildings, and even entire trees, as though to provide an answer to Schopenhauer's conundrum, to confront

the phenomenon of natural chaos with the will to aesthetic control - something like discovering the structure of cells or atoms. Where outline had once been banished, it now reappears.